comics

Archived Posts from this Category

Archived Posts from this Category

Posted by ben on 13 Jan 2009 | Tagged as: arts organizations, comics, design, video/film

Paul Richards’ article in the Washington Post advocating for a Disney-based museum show has inspired some interesting responses around the blogosphere. Greg Allen makes a plausible case that it’s nothing more than “a fanboi/critic [trying] to turn some offhand party chatter about the worst show ever into a mouse-eared museum manifesto.” Kriston Capps, in a more even-keeled post gets a bit closer to what I see as the real problem with the idea:

To admit Disney would be to open up a massive new genealogy in visual art that includes all the things that are visual but aren’t called art. So it wouldn’t be Disney and Murakami or Disney and younger fine artists but Disney and the makers of Final Fantasy or Disney and the Coca Cola designers. That might all be defensible, but it would get very confusing very quickly.

Just because something is important does not make it visual art and at the end of the day, just because something is visual art does not mean that it is represents the most important visual thing. Rather this notion of visual art you find at museums offers a streamlined conversation within visual culture, one that (one hopes) influences and is influenced by other conversations in the broader culture. But museums cannot hope to archive all those other conversations, too.

But I think it’s not just a question of what is deemed visual art or what is deemed important. The issue comes down to a more practical question of access. Museums allow us to see genuine, rare works of art from a field that was founded on prizing the unique object. When you start to show Mickey Mouse cartoons, interesting and important as they may be to visual culture, you’re showing people things they can already see in the comfort of their homes. It’s not that the material is inappropriate for the museum, but that museum treatment isn’t necessary. Without the museum, many of us would never get to see a Frank Stella except as a reproduction; but if all the museums in the world disappeared, we could still participate in the visual culture of cinema, more or less in the way it was intended to be viewed.

Maybe we’re past the point where we refuse to consider Disney or Alfred Hitchcock or Matt Groening to be “real artists,” but that doesn’t mean that the public would be well-served by seeing their work in museums.

Posted by ben on 20 Dec 2007 | Tagged as: arts organizations, comics, graffiti, responses/reviews

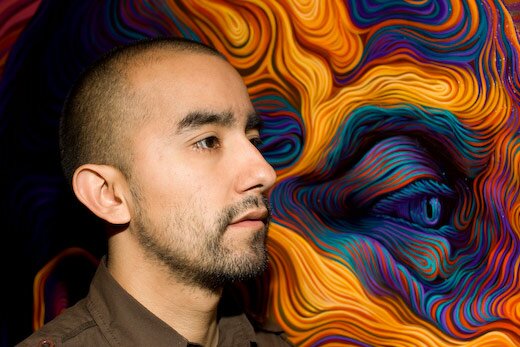

I feel bad for Alex Rubio. A month after his residency at Artpace ended, he had to put together a whole new exhibition of work for Museo Alameda. And although he pulled it off, the differences between the shows are revealing. Both exhibits are based around the idea of community; at Artpace, Rubio orchestrated an installation that combined the talents of local artists ranging from graffiti artist Shek to metal sculptor Luis Guerrero to neon and glass artist Cathy Cunningham; the Alameda mounted a two-person show by Rubio and his former student Vincent Valdez, which emphasized their shared history in San Anto (Rubio on the west side, Valdez on the south side). The Alameda show also brought in some community artists to accentuate the work with neon and sculpture, but remained primarily a showcase of the two artists’ paintings.

Let me start off by saying that both shows were successful, and anyone who hasn’t seen them yet should make the effort to drop by Artpace and the Alameda before they go down (the Artpace show runs through January 6, while the Alameda show closes March 23). At Artpace, Rubio orchestrated an installation that seamlessly blends the talents of a wide range of artists into a work that fits right into Rubio’s oeuvre. Organizing a community of artists around a singular vision is no easy task, and Alex Rubio pulled it off.

The Museo Alameda’s exhibit, curated by Benito Huerta, has a different goal: to juxtapose the work of two San Antonio artists with common yet divergent paths. The reason this show works is that the cinematic drama of Vincent Valdez’s work provides an effective counterpoint to the twisted, psychedelic visions of Alex Rubio. Both artists embrace the gritty reality of the streets in their native barrios, and bring into full view both the pride and the laments of their cultural heritage. Yet the divergent means through which they approach these realities tinges the community they depict with two distinct flavors. Valdez’s aesthetic could be drawn from the films of Scorsese, with their visceral impact and complex, yet direct, realism. At the same time, Valdez weaves a contemporary symbolism into his work, imbuing it with a sense of cultural depth. Rubio, on the other hand, seems to owe more to the psychedelic exploration of underground comics or even rock concert posters, while bringing this stylistic vocabulary to a new level of complexity and vibrant energy.

But when your eye drifts from the paintings, the rough edges start to become apparent. A huge map of San Antonio reminiscent of a pirate treasure map is prominently installed in the exhibit, highlighting the artists’ neighborhoods and showing the locations of significant events in their lives. Besides being difficult to read, this map, when at long last it is deciphered, brings very little to the paintings, which clearly convey a coherent experience of the world. Neon hands designed by Valdez forming the “signs” for the North, South, East and West sides feel tacked on; and a sculpture of the boxer in Valdez’s paintings lacks the emotional depth and formal strength of the original.

Still, this show is about the paintings, and the paintings succeed.

Posted by ben on 13 Dec 2007 | Tagged as: comics, video/film

Check out some great images (and video) of Mike Kelley’s new installation at Jablonka Galerie, which deals with the representation of Superman’s home town, Kandor, in the DC comic books. This press release explains the show more fully.

Posted by michelle on 19 Oct 2007 | Tagged as: books, comics, responses/reviews

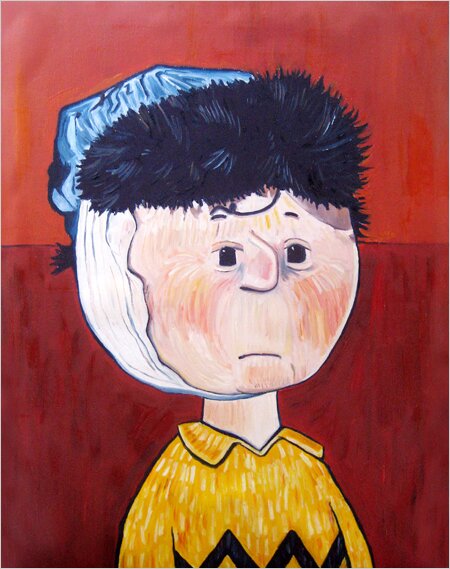

NY Times ran a great article about the tortured life of Peanuts’ creator, Charles Schultz. This graphic by Kim Scafuro had me in stitches. A new biography by David Michaelis spurred the article. Michaelis paints a melancholic picture of the beloved cartoonist, seven years post mortem. Reporter Randy Kennedy makes good use of references from Balzac to Toulouse-Lautrec with lots of levity in between. The last line lets Schultz speak for himself and it makes me wonder if Pig Pen wasn’t Schultz walking around with a little, scribbly cloud hovering above him everyday.

Another excerpt?

Posted by ben on 12 May 2007 | Tagged as: comics, mustaches, net.art

Nails is one of the more successful Flash-based net.art projects I’ve come across. This unnerving yet hilarious series of dada self-portraits by Han Hoogerbrugge has been running since 2002. This series grew out of Modern Living / Neurotica, which began life in 1996 as animated GIF loops, but later migrated into interactive Flash. Throughout both projects Hoogerbrugge uses a primarily grayscale pallet to illustrate various states of psychological tension through terse, punchy cartoons. The soundtracks are also particularly effective at creating eerie atmospheres which allow the little animations to get under your skin.

Posted by ben on 16 Jan 2007 | Tagged as: comics

I went to the Steiren Compound Halloween Party this year doing my best to look like Krazy Kat; the reference was lost on all but a few. This puzzled me, as I always think of George Herriman as one of America’s most striking and original artists, despite his predilection to work in a maligned art form. To spread the word, I thought I’d write a little post on Krazy Kat. But E. E. Cummings beat me to the punch about sixty years ago, so here’s an excerpt from his essay on one of America’s first works of surrealist art:

What concerns me fundamentally is a meteoric burlesk melodrama, born of the immemorial adage love will find a way. This frank frenzy (encouraged by a strictly irrational landscape in perpetual metamorphosis) generates three protagonists and a plot. Two of the protagonists are easily recognized as a cynical brick-throwing mouse and a sentimental policeman-dog. The third protagonist — whose ambiguous gender doesn’t disguise the good news that here comes our heroine — may be described as a humbly poetic, gently clownlike, supremely innocent, and illimitably affectionate creature (slightly resembling a child’s drawing of a cat, but gifted with the secret grace and obvious clumsiness of a penguin on terra firma) who is never so happy as when egoist-mouse, thwarting altruist-dog, hits her in the head with a brick. Dog hates mouse and worships “cat”, mouse despises “cat” and hates dog, “cat” hates no one and loves mouse.

Ignatz Mouse and Offissa Pupp are opposite sides of the same coin. Is Offissa Pupp kind? Only in so far as Ignatz Mouse is cruel. If you’re a twofisted, spineless progressive (a mighty fashionable stance nowadays) Offissa Pupp, who forcefully asserts the will of socalled society, becomes a cosmic angel; while Ignatz Mouse, who forcefully defies society’s socalled will by asserting his authentic own, becomes a demon of anarchy and a fiend of chaos. But if — whisper it — you’re a 100% hidebound reactionary, the foot’s in the other shoe. Ignatz Mouse then stands forth as a hero, pluckily struggling to keep the flag of free will flying; while Offissa Pupp assumes the monstrous mien of a Goliath, satanically bullying a tiny but indomitable David. Well, let’s flip the coin — so: and lo! Offissa Pupp comes up. That makes Ignatz Mouse “tails.” Now we have a hero whose heart has gone to his head and a villain whose head has gone to his heart.

This hero and villain no more understand Krazy Kat than the mythical denizens of a two dimensional realm understand some three dimensional intruder. The world of Offissa Pupp and Ignatz Mouse is a knowledgeable power-world, in terms of which our unknowledgeable heroine is powerlessness personified. The sensical law of this world is might makes right; the nonsensical law of our heroine is love conquers all. To put the oak in the acorn: Ignatz Mouse and Offissa Pupp (each completely convinced that his own particular brand of might makes right) are simple-minded — Krazy isn’t — therefore, to Offissa Pupp and Ignatz Mouse, Krazy is. But if both our hero and our villain don’t and can’t understand our heroine, each of them can and each of them does misunderstand her differently. To our softhearted altruist, she is the adorably helpless incarnation of saintliness. To our hardhearted egoist, she is the puzzlingly indestructible embodiment of idiocy. The benevolent overdog sees her as an inspired weakling. The malevolent undermouse views her as a born target. Meanwhile Krazy Kat, through this double misunderstanding, fulfills her joyous destiny.

– E. E. Cummings