wordy

Archived Posts from this Category

Archived Posts from this Category

Posted by ben on 08 Jan 2010 | Tagged as: conceptual art, video/film, vs., wordy

Conway’s Game of Life translated into one line of APL.

“Rules of Inference” by Mel Bochner

Posted by aaron on 14 Jan 2009 | Tagged as: arts organizations, essays, in yo face, music, mustaches, possibilities, public art, r.i.p., rock!, wordy

Manuel Diosdado Castillo, Jr. tragically succumbed to lung cancer on January 6th at the age of 40 – a matter of weeks after receiving the diagnosis – leaving behind a remarkable legacy of music, public artwork, of pride in and a powerful sense of responsibility for his beloved Westside San Antonio barrio. Manny was, for nearly twenty years, a singular presence in both the underground music scene in San Antonio (whose spiritual epicenter is marked by the centuries-old live oak tree at his favorite local dive/venue: the legendary, much-missed Tacoland) and in the non-profit community organization he built, originally as an offshoot project of Patti & Rod Radle’s Inner City Development, but which quickly blossomed into San Anto Cultural Arts.

My friendship with Manny goes back to a spontaneous garage rehearsal circa 1991. Marshall Gause and I were fruitlessly waiting at my folks’ house for some now forgotten drummer we wanted to try out, as our last band line-up hadn’t worked out. Marshall suggested trying to get in touch with this guy he had played a couple of times with the year before – they had enjoyed it, but it didn’t go anywhere as Manny soon left for New Orleans to follow Academic Pursuits. Marshall had a hunch he might be back in town now. After a few calls, the hunch was confirmed and we had a drummer on the way.

That first rehearsal (guitar, bass, & drums – singer Terry Brown had to work) immediately revealed an undeniable chemistry between Marshall’s hippy-punk musicologist guitar explorations, my intuitive but rudimentary bass playing (which, lucky for me, sounded better than it had much right to thanks to my chronic music obsession, a plethora of interesting audio exposure at a job selling used records, and especially Marshall’s unpretentious ability to cover for my lack of formal musical knowledge,) and Manny’s balls-out, hit-the-drums-hard-enough-to-break-at-least-one-head-per-session-but-always-dead-on-the-beat style, using complex rhythms even formally trained jazz drummers wouldn’t have the nerve to try. He was, and remains, one of the fastest, most precise drummers I have ever seen (even faster when he was nervous,) augmented by the physical strength to just bash the hell out of his drums – a steamroller cross between John Bonham, Neil Peart, Mitch Mitchell, George Hurley and Elvin Jones. All on a minimal and creaky drum set usually somehow held together with yarn.

That afternoon we quickly bonded musically over our mutual love for Rush, The Plugz, Esteban Jordan, Thin Lizzy and especially The Minutemen. Spontaneous jams we engaged in that day became the basis for numerous songs later fully developed and forming the initial base of our oeuvre (some still included in the set list at the time the band imploded.) In short order, we brought Terry back into the circle, sat around with some Lone Stars or whatever was cheap that day and soon agreed to call ourself El Santo, in homage to the legendary Mexican lucha enmascarada/film star who never lost a match.

Posted by thomas-cummins on 08 Jan 2009 | Tagged as: essays, responses/reviews, wordy

Just saw ‘Doubt‘ and it’s definitely worth a trip to the theater but I’m interested in Winkleman’s response to the film and his concern with the word doubt and how artists are suffering from a lack of certainty as well as religion – “Consider this an open thread on vital religious/spiritual impulses, art making, and whether or not any of this is new.”

Indeed, this is not new, and doubt has always been at the root of philosophy. The father of Western philosophy, Socrates, once famously agreed he was the wisest man in Athens because he knew that he knew nothing. Cartesian doubt was named after the father of Modern philosophy, Rene Descartes, and his credo to “doubt everything” (”de omnibus dubitandum est”) in an attempt to find a foothold of certainty on which his philosophy could firmly stand. Descartes noted that, more often than not, things are not the way they appear to be and that our senses often fool us – a stick might seem bent under water or we often awake from dreams that we mistaken for reality and, in the end, we could never truly know if Surrounded by all this uncertainty, however, we can never doubt the fact we are doubting and this naturally led to his bedrock “I think, therefore, I am.” Eventually, Critical Theory would derive its name from Kant’s ‘Critique of Pure Reason‘ (and Judgment) in his criticism of possible knowledge and in a response to David Hume’s radical skepticism.

Winkleman notes “how debilitating uncertainty is” but doubt has proven itself the greatest ally to artists. Marxist theory contends that the primary function of art is social criticism and it is certainly true that art perpetually doubts the ideology of the reigning majority. Indeed, Kierkegaard points out that the word ‘doubt’ is etymologically related to the word ‘double’ – our meaning is always duplicitous – there is always two sides to every story, two sides to every coin, and as Nietzsche would write “there are no facts, only interpretations.” Even the sacred realm of science is not immune from the clutches of doubt and prevailing Theories of Relativity and Quantum Theory actually contradict each other and are probably both wrong. Indeed, our everyday trust in science is a lot closer to a religion than we like to admit. Science is a modern religion of high probability but it can never fully erase doubt. Karl Popper would attack the ultimate futility of science when he harshly pointed out “Science is perhaps the only human activity in which errors are systematically criticized and… in time, corrected” and “all we can do is search for the falsity content of our best theory.” Indeed, Einstein agreed with this final assessment and concluded, himself, that “Only daring speculation can lead us further and not accumulation of facts.” Daring speculation just happens to be the primary realm of the artist. Doubt has certainly been around for a long time, but only in our most enlightened moments.

Texas Public Radio will have a more comprehensive review of “A History of Doubt” at 10am on Sunday. Tune into 89.1 FM to hear the radio show “Speaking of Faith” with poet and historian Jennifer Michael Hecht.

Posted by ben on 05 Jan 2009 | Tagged as: arts organizations, essays, possibilities, responses/reviews, wordy

Edward Winkleman posted a short essay on Saturday, which, in short, claims that the future of the art world is in fact the present of the art world. Citing Barack Obama, Winkleman ties the conventional wisdom about the impact of the internet on contemporary society to the current diaspora of the art world. While the underlying premise is not particularly new or insightful, it was a point that needed to be made: art world observers still looking for “the next big thing” need to take a deep breath and accept that fragmentation is here to stay; and this is, in fact, “the next big thing.” This isn’t a crisis, it’s just a way of being. Winkleman catalogs the effects our database-driven culture is having on the art scene, from curating to collecting to artmaking, and announces that these ripples will only expand as time marches on. What this means is that those looking for a new style or idea to dominate contemporary art culture will be disappointed. Poststructuralism is here to stay, and we’ve only begun to tap its implications.

Fair enough, but I think there’s another point to made here (which is perhaps just a shift in emphasis). Winkleman’s essay focusses on the anachronism, contrasts, and tension bred by a process that revels in referencing the Old Masters alongside contemporary pop culture, in drawing improbable threads through history. He emphasizes the information gathering, the cataloging, the futile but fascinating battle against being overwhelmed by the shear amount of information available to us.

But I think what’s most interesting about our current moment is the ways in which it potentially frees us from these obsessive chases, and actually opens up space for more genuine personal interactions. That might sound counter-intuitive at first, but the fact that there’s no longer a dominating formal or conceptual framework allows us to experience art on more personal terms. As a society, we may no longer reject certain styles of work as “unserious” — we may be forced to accept abstract expressionism alongside minimalism alongside realism alongside surrealism ad nauseum; but as individuals we are more free to just focus on the work that reaches us, rather than struggling to understand paint splatters because Greenberg told us to. And whatever style happens to appeal to you, whether it’s Mark Bradford, Walt Disney, Johathan Ive, Cecil Taylor, Bernard Leach or Outkast, there’ll be plenty of opportunities to make personal connections with others who care about the objects of your quirky taste. We can be more sincere about art if we allow ourselves to be.

So while Winkleman moves toward the conclusion that “art by concensus” will come into vogue, I’m more interested in how much more habitable the long tail is becoming: there are those of us interested in making the connections between styles and disciplines; and there are those whose myopic focus we leach off of to make our broad connections. For both groups, the world is becoming a , if more fragmented.

Posted by ben on 15 Dec 2008 | Tagged as: performance art, poetry, r.i.p., wordy

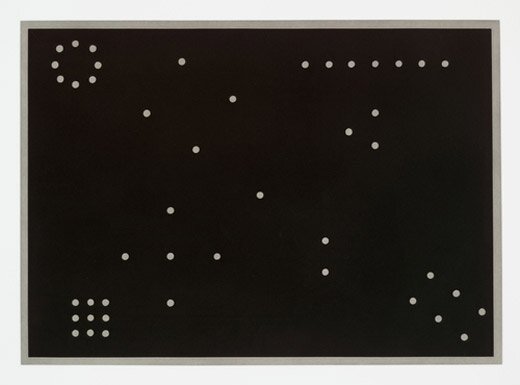

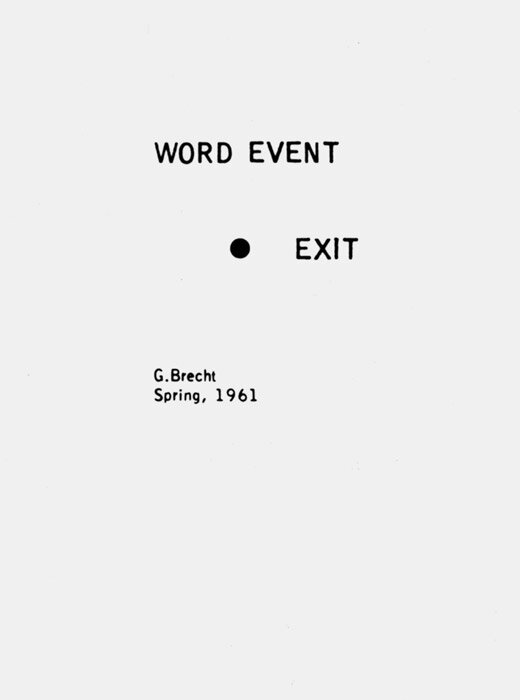

Word Event (George Brecht, 1961)

In their use of language as a device to cut into the evanescent everyday, [George] Brecht’s “insignificant and silly gestures” open an infinite universe of possibilities, just as [La Monte] Young’s precise operations move into the zones of the minimal and the series, of the same but inevitably different because virtually interminably—the line or the sound would go on in some sense “forever.” In both, the event is pared down to a minimum: a simple, basic structure that can be endlessly reenacted and reinscribed in new contexts, different in each instance and yet retaining a certain coherence. Inevitably calling to mind Lawrence Weiner’s highly condensed and yet generalizable “statements,” Brecht’s and Young’s most interesting scores reduce language to a kind of object, but also establish it as a kind of repeatable, replaceable structure, open to unlimited, unforeseeable realizations.

— Liz Kotz,

Posted by justin on 07 Sep 2008 | Tagged as: adventure day, wordy

Posted by michelle on 30 Aug 2008 | Tagged as: interviews, wordy

EMV: Kristy, you’ve been an artist primarily working in the sculptural realm. Ever since you won the Artist Foundation Grant [correct me on the title/specifics], seems like you’ve been getting steady shows and making stronger work. Why are so many objects gilded? I know Glasstire posted a nice photograph of the gilded dog bone, but they didn’t let you explain yourself. Want to do that here?

EMV: Kristy, you’ve been an artist primarily working in the sculptural realm. Ever since you won the Artist Foundation Grant [correct me on the title/specifics], seems like you’ve been getting steady shows and making stronger work. Why are so many objects gilded? I know Glasstire posted a nice photograph of the gilded dog bone, but they didn’t let you explain yourself. Want to do that here?

KP: Yes, in 2007 I was the first recipient of the Chez Bernard grant for underrepresented artists. This is a grant made possible by Mr. James Lifshutz on behalf of his father Bernard Lifshutz for the Artist Foundation of San Antonio. The foundation itself is the brainchild of Betty Ward and Patricia Pratchett. You know I have to say here, that the opportunity I was provided by this group of people/artists/patrons really helped a dream come to fruition. I mean I got to have my hand in every part of making that show happen. It was pretty damn close to…here’s some money, find a place, make some work, and let us know what you need, to set it up the way you imagine it. That kind of freedom and support was something I had never experienced befor. It was empowering. I would encourage any artist to check out the A.F. website and learn more.

I’ve worked for the past 4 years as an assistant to art conservator, Anne Zanikos. My duties at work are primarily frame restoration and conservation of polychrome wood objects and so it was here that I was introduced to gilding. Somewhere along the way using gold leaf in my artwork became inevitable. I had seen what it could do for a surface but also, the preparation involved before an object is gilded is quite meticulous and labor intensive. This process forced me to be disciplined, and really learn the craft in order to be rewarded in the end with this beautiful glowing object. The whole tactile experience presented itself as an invitation. In contrast, using the material in my sculpture I bring my understanding of the craft but sometimes allow myself to be more free or loose in the handling…in hope for some poetry along the way. I guess it would be good to note here that gold being “arguably” one of the most precious commodities in the world really serves its purpose when using it in juxtaposition with an everyday, overlooked or forgotten object.

EMV: Being based in San Antonio, do you find it difficult to gain curatorial and critical attention outside of this South Texas sphere?

EMV: Do you consider yourself a feminist artist? What does that mean in 2008 anyway, with the porno Martha Rosler image as the catalog cover for all things documented as feminist art [WACK: Art and the Feminist Revolution]?

KP: I hope that everyone who hears this name goes and looks it up – HARMONY HAMMOND. Now that’s a feminist artist.

Posted by michelle on 25 Aug 2008 | Tagged as: interviews, wordy

EMV: So, tell me about “Tiny Acts of Immeasurable Benefit” and how you came up with this new body of work.

EMV: So, tell me about “Tiny Acts of Immeasurable Benefit” and how you came up with this new body of work.

KP: I have been thinking about making this body of work for a couple of years. After “Bitchen [Pell's art installation at Artpace in 2007],” I thought I had solved my problem of how to frame my work- kind of to work as a story teller and flesh it out with artifacts and documentation. But sometimes I just get a small idea- kind of a flash image and want to make a piece that breaks my heart- and I am interested in describing a culture of acceptance and cooperation. So, that’s what these pieces are. Sure, there is bitterness, too, but that is because we are looking at the pieces through our own eyes. We project the irony on them. They don’t point out any sort of contradiction within themselves (except for the prints). Sure, maybe I will make sort-of-narrative shows like “Bitchen” in the future…

EMV: I saw you walking around La Tuna inside a mirrored box. it’s a playful and striking piece that seems half architecture and half Dadaist costume. Why did you make this piece and how is it connected to your ongoing work?

KP: I have been interested in the re-emergence of the Islamic headscarf by second generation Americans and Europeans as a way of asserting a religious identity, especially since a lot of their moms don’t wear them. How much of it is simply rebelling against parents, a new identity, or is it the same impetus that makes teens still wear the black trenchcoat after Columbine (oooooh an arab, scary)? I know it is also a profound religious resurgence for many, but I’m sure there is a mixture going on- then I extended it to the burqa. And thought, what if I made a burqa that had the opposite effect from wearing one would in San Antonio today- one that actually made the woman wearing it become a reflection of everything- so that it fits in everywhere and everyone loves the wearer because it reflects the viewer? But i didnt make a flowing burqa because thats diadactic and not funny. So i made a box, then it looked like a disco-ball-duck-blind-confessional, so i called it “Blind for Everything.” Then it had a sort of cool wordplay, you know: blind, camouflage, another piece about how we build ourselves by making choices out of what we see (like Mick , like “Bitchen”).

EMV: How has your vision changed, if at all, since your residency at Artpace?

KP: I have made the same work since I was a kid- about how I see myself and how class and background combine with the sort of dreamy role-modeling we can create from literature, TV, magazines and religion. To me, the most typical thing an American can say is “I’m not your typical american,” to think you are not a type, to think you built yourself out of dust , to see yourself as a Horatio Alger of coolness, artistic integrity, wealth, musical tastes, fashion. I haven’t had the budget I had at Artpace so I have to put some of my more expensive projects on hold till i can save up.

Posted by ben on 17 Aug 2008 | Tagged as: poetry, wordy

A Man of Words

His case inspires interest

But little sympathy; it is smaller

Than at first appeared. Does the first nettle

Make any difference as what grows

Becomes a skit? Three sides enclosed,

The fourth open to a wash of the weather,

Exits and entrances, gestures theatrically meant

To punctuate like doubled-over weeds as

The garden fills up with snow?

Ah, but this would have been another, quite other

Entertainment, not the metallic taste

In my mouth as I look away, density black as gunpowder

In the angles where the grass writing goes on,

Rose-red in unexpected places like the pressure

Of fingers on a book suddenly snapped shut.

Those tangled versions of the truth are

Combed out, the snarls ripped out

And spread around. Behind the mask

Is still a continental appreciation

Of what is fine, rarely appears and when it does is already

Dying on the breeze that brought it to the threshold

Of speech. The story worn out from telling.

All diaries are alike, clear and cold, with

The outlook for continued cold. They are placed

Horizontal, parallel to the earth,

Like the unencumbering dead. Just time to reread this

And the past slips through your fingers, wishing you were there.

– John Ashbery (from )

Posted by ben on 08 Jan 2008 | Tagged as: design, essays, graffiti, responses/reviews, wordy

There’s a study making the rounds which investigates the connection between cultural consumption and social position. The findings are being trumpeted as “There’s no such thing as a cultural elite” — but this is a bit misleading. What the study finds is that first, cultural proclivities are determined by social status rather than social class (i.e. it’s more about your education and occupation than your tax bracket). Second, people tend to either seek out popular culture, or to seek out both popular and “high-brow” culture. The interesting point here is that there is no statistically significant group that pursues high-brow culture while shunning low-brow culture. So, for the most part, people are either passive consumers of culture (or “univores”), soaking up the popular types of music, theater, and art that surround them, or they are active consumers (or “omnivores”), spending time and energy pursuing the more rarefied art forms, while also enjoying the arts of the common man.

However, as the study notes, this “univore-omnivore” distinction gets a bit murky when it comes to the visual arts (there’s also another paper by the same authors that focuses specifically on the visual arts). If you clicked on the link at the beginning of this post, you probably noticed that the article in the Toronto Star suggests that the study finds that “the visual arts do not figure very high on anyone’s to-do list.” This is where things get complicated, and naturally, where the journalist gets lazy. The survey the study is based on asked about 6,000 people in Britain what kind of cultural events they attend, including things like rock concerts, jazz concerts, operas, movies, gallery openings, etc. In the visual arts, all five categories boil down to the question: how many museums, galleries, or art / craft fairs have you attended in the last 12 months? Those types of events that could be classified as popular (craft fairs and cultural festivals) actually received much lower attendance than those classified as high-brow (museums and galleries), and thus the “univore” group doesn’t really apply in this area.

The authors of the study also admit that they don’t have any data on home or street consumption of visual art (paintings, posters, graffiti, advertisements, or coffee table books). In a footnote they point to showing that in the working class home, most visual objects are either mementos or decorative objects, both of which are taken as “not artistic.” I think at this point we can begin to see the problem with these findings. Popular forms of visual art are practically defined out of existence, as cinema is grouped with theatrical arts, and all the graphic design, architecture, and other “decorative” elements that constantly surround us are taken to be something other than art. There are numerous ways to engage in visual culture besides going to galleries, museums, and craft fairs, none of which are captured by the dataset used for this study.

Posted by ben on 28 Dec 2007 | Tagged as: responses/reviews, wordy

A recent post by Edward Winkleman (via Conscientious) responding to an article in The Art Newspaper asks whether artists have a “responsibility to participate in the political debate” through their work. I dealt with this issue back in March, but it’s a complex topic that I’ve had a few more thoughts about since then.

Ed Vaizey’s article in The Art Newspaper asks why we don’t see more artists engaging with political topics from a right-wing viewpoint. Where’s the outrage, he wonders, over the hunting ban (this is a UK newspaper) in the arts community? After all, he figures, contemporary artists tend to be individualists who participate in the market, so why aren’t they more critical of leftists, who tend to restrict individual liberties and free markets? Assuming Vaizey’s characterization of artists as individualistic free marketeers is not a silly stereotype derived from a strange combination of Clement Greenberg’s writings and Sotheby’s press releases, I’m not sure why Vaizey feels that these values would lead artists to care about fox hunting. Unless, of course, he thinks that for anyone to engage in the political debate they have to buy into the expedient left-right dichotomies politicians cram down our throats.

And herein lies the problem. When people talk about an artist’s “responsibility to participate” in political issues, they are asking for engagement in a framework that is both rigid and constantly shifting. What I mean by this is that it is expected that if you support tax cuts, you should support the invasion of Iraq, and if you supported the invasion of Iraq, you should support “enhanced interrogation” (i.e. torture). On the other hand, if you support legalized abortion, then you should support gun control, and if you support gun control, you should support national ID cards. And yet the terms of the debate are constantly shifting; conservatives don’t like big government, unless George Bush wants to expand the Department of Education budget by 50%, or conduct warrantless wiretapping.

So, to come back to Vaizey, if an artist wants to sell artwork on the free market, then why doesn’t that artist oppose hunting bans, and furthermore, show some paintings making that position clear? Participating in the debate means accepting the terms of the debate, rather than critiquing them. Vaizey’s a Conservative politician, but this applies equally to those pushing for artistic activism on the left. Winkleman’s response is a little more reasonable, although I find fault with his implication that the proliferation of more right-leaning art would force those on the left to make political artwork which is more nuanced and universal. If anything, I think it would polarize the art world along the silly, manipulative lines of the political spectrum.

But I think there’s also a much more concrete, practical problem with calls for a more politicized art: timing. To take the local example of Artpace, if there is a fundamental problem with Artpace’s approach to presenting art*, it is that artists have a 3 month residency in which to create their work. It is not unusual for Artpace to bring in top-notch contemporary artists who then produce work that feels rushed, and doesn’t really compare well to their larger body of work. A three month time period is short for most artists; in the world of politics three months is an eternity. Sure, there are certain debates that have been raging for decades (such as abortion in the US), but even these debates often shift in subtle ways — we might be dealing with parental consent at one point and partial birth abortion procedures at another.

I think in many ways it is the structure of the art world that makes this kind of activist art almost impossible to pull off with any kind of effectiveness. But that structure was set up for a reason: it allows artists to deal with contemplative, complex ideas and to present unique, engaging visual experiences. The relatively slow pace of an individual exhibition means that artists working within this structure cannot engage in a rapid-fire rhetorical exchange with political pundits. Because they can’t do this, they have no hope of engaging in effective activism, unless they work outside of the gallery / museum structure. Of course artists can still raise larger political questions about war, surveillance, societal structures, and so on, but this becomes a more abstracted conversation which rises above the political minutia that pundits thrive on, so it becomes disengaged from the “political debate” of the moment.

* I say “if there’s a problem” because I think Artpace’s residency approach has many benefits, which may very well outweigh this defect, which in any case is by no means always apparent.

Posted by ben on 24 Dec 2007 | Tagged as: responses/reviews, wordy

In yesterday’s New York Times, Roberta Smith finds a strange bone to pick with the art world’s use of the word practice (as in, “I’m getting an MFA to take my practice to the next level”). Her entire critique seems to stem from the equation of this use of the term with the usage of doctors and lawyers, which, for her, “turns the artist into an utterly conventional authority figure.” That Smith would choose this particular word to harp on is baffling to me, considering all the superfluous, obtuse language thrown about in art-critical circles. But it is the form her critique takes that really bothers me.

There are a lot of preconceptions and implications to unpack here, and Andrew Berardini at The Expanded Field has already written a fairly long response to the piece. I’ll start by noting that Smith doesn’t introduce any kind of etymological arguments in her article, and she might be jumping the gun by assuming that when artists talk about their practice it is equivalent to a dentist talking about his practice. As one of The Expanded Fields’ readers points out, it is common for Zen Buddhists to talk about their spiritual practice (which often includes artistic pursuits). Smith does introduce the notion that artists could be using this term because it emphasizes routine over revelation. Berardini’s defense of the usage falls along similar lines; he points out the liberating effects of valuing the process of making art over the product. And this is exactly the point of the Buddhist usage: you don’t have a static faith, you are engaged in an evolving practice.

An important implication of Smith’s frustration with practice is that it points to a desire to ignore the value of craft in an artist’s work. She doesn’t want the artist to be an authority on how to make objects with certain materials; she wants the artist to “operate outside accepted limits”; to constantly innovate. She wants artists to be messy, rather than to know what they are doing. That’s all well and good, artists should take more risks than doctors, but it is often the process of developing a craft that leads to important artistic breakthroughs. As Tyler Green pointed out recently, Matisse worked very conservatively in his early painting, and indeed it is rare to find innovative artists who didn’t initially work in timid ways. It is Marek Cecula’s very knowledge of commercial ceramic production that allows him to subvert the process as an artist.

It would be interesting to learn when practice began to be used in the way that riles up Roberta Smith so much, and what motivated those who drove the change. To me it seems much more likely that the common understanding of practice in the art world derives from the Buddhist usage (or something similar) than from the usage of the white collar professional community. Even if this etymology were resolved, we would still have the question of whether using practice in this way makes those outside the art community associate artists with lawyers, but this will have more to do with how artists go about doing their work, than the word they use to signify it.

Posted by ben on 14 Dec 2007 | Tagged as: books, essays, vs., wordy

“Prosaically, lunk-literal-mindedly, I’ve wondered to what extent Pollock was being subliminally influenced by the color images of telescopic deep space suddenly proliferating in all the popularizing magazines and books and movies of the period. And, too, I’ve wondered about the human scale — the place of the human in the unfolding drama. Standing before such paintings, I can get to feeling positively infinitesimal (less than minuscule, a merest speck, utterly, in Greenberg’s phrase, “beside the point”); or, alternatively, as my eyes sweep the canvas and my mind identifies, momentarily, with the glory of the painting’s making, I can get to feeling almost godlike. One is reminded of the various self-dramatizing films of Pollock around the time he was making those paintings — a Colossus striding purposefully from side to side, pausing, stabbing, hurling the universe itself into existence.” — Lawrence Weschler,

“Henceforth, when man is for once overcome by the horror of alienation and the world fills him with anxiety, he looks up (right or left, as the case may be) and sees a picture. Then he sees that the I is contained in the world, and that there really is no I, and thus the world cannot harm the I, and he calms down; or he sees that the world is contained in the I and that there really is no world, and thus the world cannot harm the I, and he calms down. And when man is overcome again by the horror of alienation and the I fills him with anxiety, he looks up and sees a picture; and whichever he sees, it does not matter, either the empty I is stuffed full of world or it is submerged in the flood of the world, and he calms down.

“But the moment will come, and it is near, when man, overcome by horror, looks up and in a flash sees both pictures at once. And he is seized by a deeper horror.” — Martin Buber,

Posted by ben on 27 Nov 2007 | Tagged as: essays, poetry, wordy

I recently picked up Walter Bejamin’s . He’s one of those writers who eloquently expounds some fascinating ideas, but often doesn’t offer much in the way of evidence. In his essay The Task of the Translator, Benjamin asserts that “It is the task of the translator to release in his own language that pure language which is under the spell of another, to liberate the language imprisoned in a work in his re-creation of that work. For the sake of pure language he breaks through decayed barriers of his own language. Luther, Voss, Hölderlin, and George have extended the boundaries of the German language.” Although he points us to examples of what he is talking about, he stops short of explaining what about these authors’ translations illustrates his point (he does, at other points in the essay, talk specifically about Hölderlin’s translation style, but in a way that is abstract enough as to not be really convincing to someone, like myself, who can’t read German).

Because of these concerns I was particularly glad to come across this essay by Seamus Heaney in the Guardian recently (via The Page). Heaney illustrates quite clearly how translations of English poetry (Shakespeare, Tennyson and Longfellow) influenced Japanese verse in the late nineteenth century; and how, a few years later, under the influence of translations of Japanese haiku, Pound and Eliot helped change the way the western world looked at poetry, giving birth to Imagism. Heaney then compares traditional Japanese verse to Old Irish verse, pointing out that the seeds of this “Japanese” vein of writing had also been buried in the western tradition.

But what I’m most interested here, coming back to Benjamin, is the notion that these were translations that Eliot and Pound were reading. Perhaps there is a sense in which the translators of Shakespeare into Japanese or Basho into English deserve more credit for helping to move the target languages in a certain direction than do the poets writing in those languages. Heaney clearly isn’t setting out to prove this point, and he certainly doesn’t demonstrate it, even inadvertently. It could very well be that Benjamin’s notion that the “character” of a particular language is actually shifted by (good) translations from another language is faulty, and that this blending of traditions has more to do with how writers choose to use a language rather than its underlying character. However, I think some of the evidence Heaney introduces about the historical development of poetic traditions could serve to bolster Benjamin’s argument.

The more I think about these ideas, the closer I get to the black hole of linguistics debates (especially when pondering Benjamin’s appeal to “pure language”), so I think I’ll stop here, before I get sucked in.

Posted by ben on 06 Sep 2007 | Tagged as: responses/reviews, wordy

Copyright law has given essential protections to artists as long as it has been around, allowing for a legally enforced structure within which to distribute reproductions of artwork. In recent years, with the rise in popularity of sampling and appropriation, it has also been seen as a major obstacle to many artists. Hence the rise of ‘copyleft‘ and Creative Commons, which created a sub-structure within existing copyright laws allowing for certain kinds of reuse and redistribution, while keeping ownership of the work in the hands of the original artist.

Meanwhile, publishing companies, who see copyrighted work as their lifeblood, have struggled to extend and strengthen copyright laws. We have seen the lifespan of a copyright extend from a modest 14 years (with the possibility for a 14 year extension) at the founding of the United States to the entire life of the artist plus 75 years today.

Recently, however, free speech and free culture advocates have been trying to fight back the rising tide of copyright regulations. A major decision was handed down yesterday by the 10th Circuit Court of Appeals regarding these expansions of copyright. They relate specifically to the Uruguay Round Agreements Act (URAA) enacted under Bill Clinton. This act placed certain foreign works under US copyright which had previously been considered part of the public domain in the US. The 10th Circuit found in Golan v. Gonzales that taking works out of the public domain retroactively is unconstitutional requires further scrutiny, invalidating this section of the URAA remanding the URAA to the District Court for First Amendment review.

Lawrence Lessig (who argued the case) believes that this will have major implications for the Supreme Court review of another case, Kahle v. Gonzales, which seeks to overturn the shift from opt-in copyright to opt-out copyright (that is, it used to be that you had to specifically mark something as copyrighted to take it out of the public domain; now, works are copyrighted by default unless the creator specifically chooses to place it in the public domain). More analysis of this important decision can be found at Balkinization.

These decisions have potential to move the balance closer to the ‘culture wants to be free’ side of things, and further from the ‘culture is property’ side, limiting the kinds of laws Congress can pass to further lock down the free flow of information and art.

Posted by justin on 24 Jul 2007 | Tagged as: art paparazzi, bird flu, possibilities, responses/reviews, silliness, wordy